Because Blogger is owned by Google, I have been long been expecting my posts to be censored, so I have them all backed up. But in all of 2024, only one post was deleted. A post about Jason Christoff.

And strangely my blog now has some strange formatting bugs that started at the same time as the post was censored. No matter what I do in the advanced theme settings, I no longer seem to be able to change the colours of the unvisited links which are now stuck on an unreadable dark blue. It may be coincidence, but I can't help wondering if after a year of working perfectly, Google wanted me to stop using their platform? Odd...

It's an interesting example of censorship... Ironically, in censoring this particular post, Google have rekindled my interest in posting online. Why do they care so much? Which part of this information do these globalist data collecting scum fear the most?

My original post was a summary with a link to his excellent list. But if Goggle are censoring him to this extent I'm even more interested now! What exactly was it in my post that triggered Google's AI censorship?

HERE IS MY ORIGINAL POST - IF THIS GET CENSORED AGAIN I WILL TRY TAKING SOME PARTS OUT - AND THAT MAY BE REVEALING:

A GREAT LIST

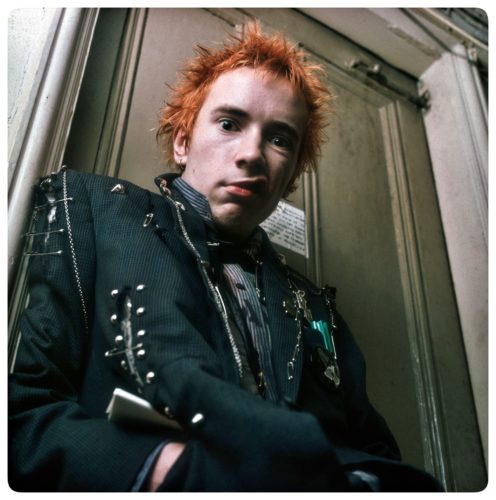

While investigating the rabbit hole that is mass poisoning

using coffee, earlier this year I stumbled upon a researcher called

Jason Christoff

Almost all the popular names in the so called alternative health

movement are sponsored and therefore controlled by deep state gate

keepers like The

Wellness Company, who keep them in line by funding them, as well

as selling coffee. Jason Christoff appears to be a lone voice in the

wilderness exposing what is really going on with coffee.

And unlike most of those other "influencers" I don't get

the impression he is a shill. Check out his list of 20

Truths to Make Your Life Better In 2025 No controlled opposition

puppet would post this stuff!

In this list he covers conventional

medicine, government, viruses, taxes, fluoride, school, TV, vaccines,

evolution, genders, alcohol, coffee, marijuana, media, mind control,

Ukraine, Covid 19 and several other topics in a series of concise

summaries. The post URL was originally "The Top 25 Lies" so

I suspect he toned the list down a bit and cut it back to 20, but he

strikes me as a legit voice exposing this stuff, which is very rare.

In fact he has inspired me to do a longer list

exposing all these lies and a bunch more, but I'm having a break from

"conspiracies" at the moment.

Truth is, I've been going on about this stuff

online for more that 20 years, and I'm a total burnout, with almost

no audience left anyway, so it's probably time for me to shut my trap

and find some good sources to recommend instead. A great thing about

Jason Christoff is that despite being grey listed he still has

a large online audience.

Here is what he said about coffee:"Coffee is

healthy". Absolute inversion, completely false. Coffee is the #1

most effective mind control substance ever shoehorned (via social

engineering) into our society. Not only does daily caffeine

consumption make you extremely unhealthy and guarantees your

premature death, but caffeine also primes the human nervous system to

be extremely suspectable to all forms of mind control.

https://www.jchristoff.com/blog/the-top-25-lies-many-people-are-still-believing-in-2025